Prompt: “Write a single sentence summarizing why cryptographically-signed provenance information matters in the context of AI-generated content.”

ChatGPT: “Cryptographically-signed provenance information matters in the context of AI-generated content to establish trust, transparency, and authenticity by providing a verifiable record of the content’s origin, authorship, and creation process.”

That’s a great point, but did ChatGPT really say that, or did I make that up to trick you into reading this article? I could show you a screenshot of that exchange to try to convince you …

… but what good would it do, when it’s so easy to produce convincing fakes?

In this article, I’ll explain how and why AI vendors such as OpenAI should adopt techniques that make it possible to build strong associations between AI-generated content and its provenance information, with a particular focus on text — or “GPT-born content” — which presents unique challenges.

While recent advances in the standardization of cryptographically-signed provenance techniques help make this possible, the accelerated pace at which generative AI-based products are being put in front of consumers makes it necessary, as one of the many steps the industry could take to help prevent and reduce harm.

Papers, please

Maybe it is because I am an immigrant in the United States, and therefore am used to having to repeatedly prove who I am, where I come from, and why I am here, but I find similarities in the methods government agencies employ to figure out whether I belong here, and the problem at hand.

Every time I travel back to the United States, I need to have my passport with me, which shows where I come from, but also my green card, which shows why I am here. If I were to lose these documents, my biometrics, collected earlier on, could be used to identify me and make an association between myself and my immigration status and history.

Generative AI is crossing a yet-to-be-defined border between statistics and human creativity, and while this is something we should welcome, we can also ask that it identify itself when it does so. Cryptographically-signed provenance information, embedded in a file or archived on the server side, could help achieve that goal. After all, why would we make humans jump through so many - and sometimes unjustified - hoops, but simply trust AI output?

Enter C2PA

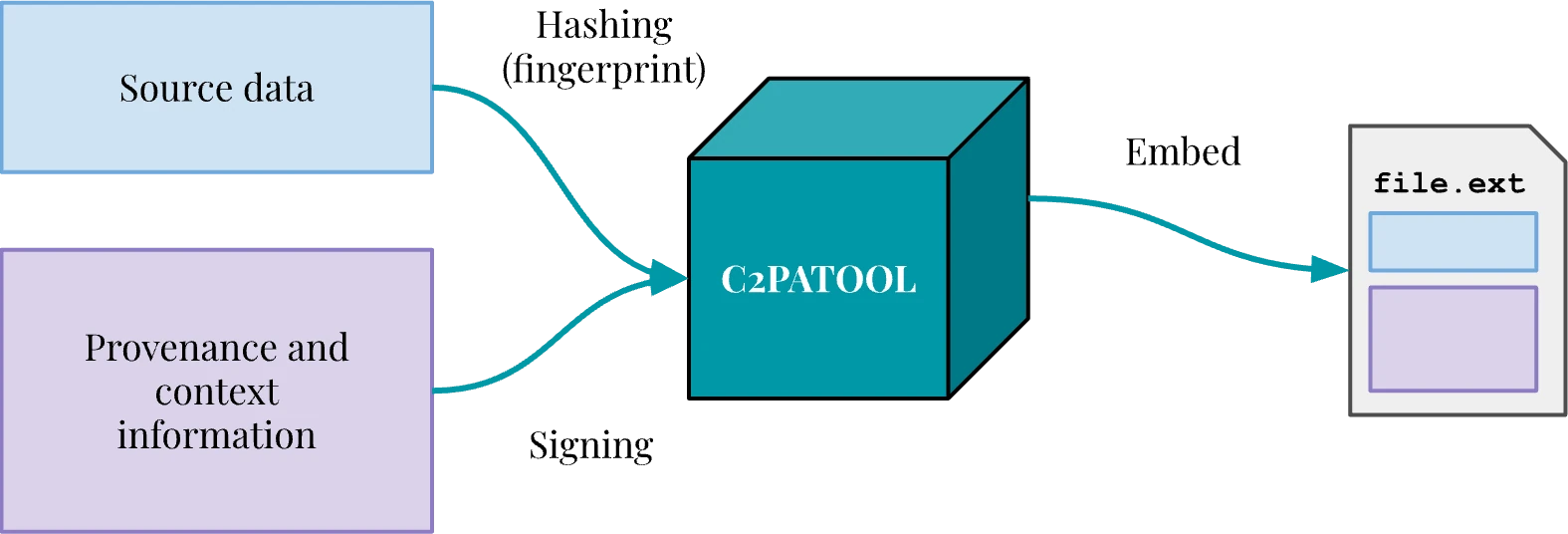

The “Coalition for Content Provenance and Authenticity”, or C2PA, is the result of an alliance between the software industry, newsrooms, and non-profit organizations to design and implement technical standards to combat disinformation online. C2PA is also the name of the specification the coalition put together, which allows for embedding cryptographically-signed provenance information into media files. The Content Authenticity Initiative — the Adobe-led arm of C2PA — has developed and released open-source tools to allow the public to develop applications making use of this emerging standard.

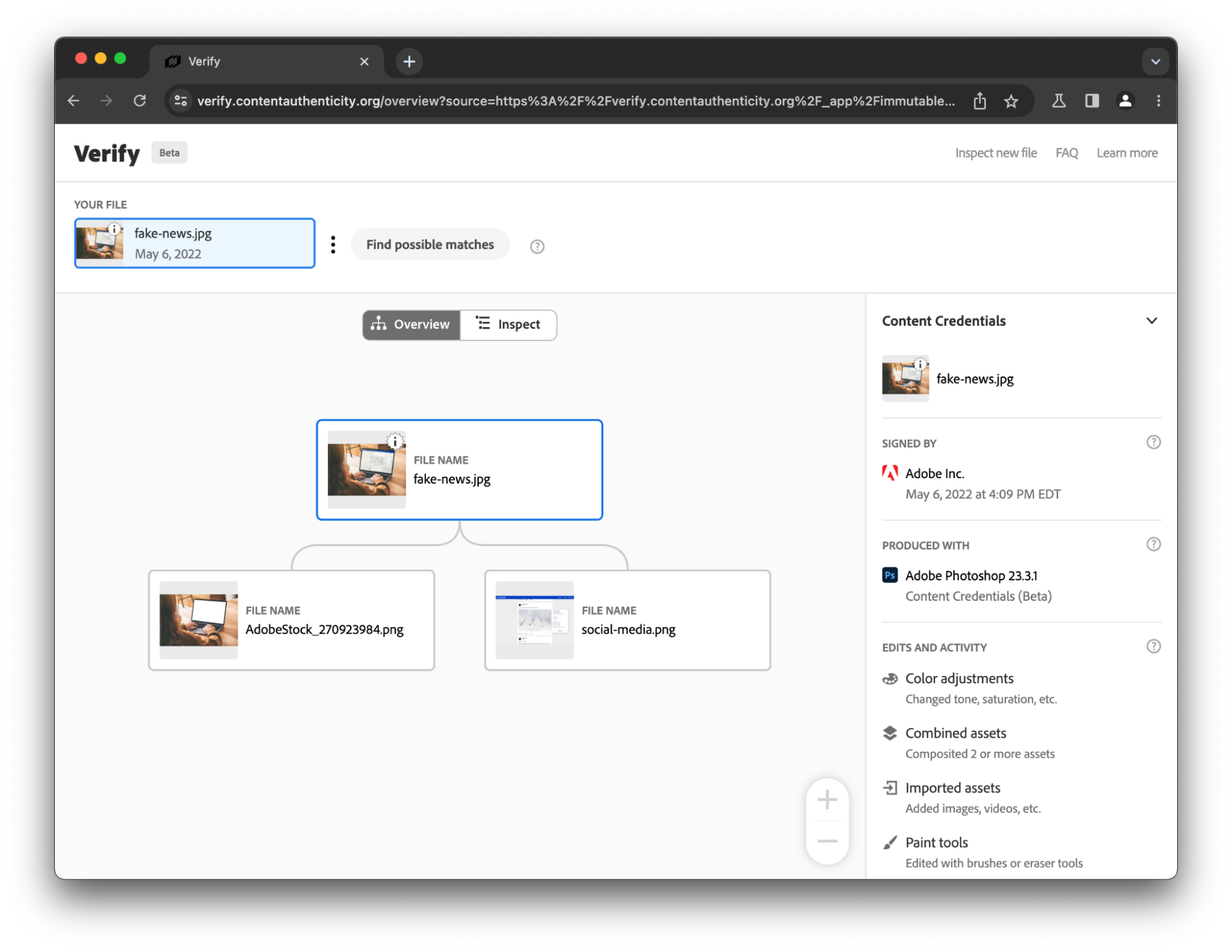

That concept is powerful in that it allows an image, a video or audio file to tell us reliably where it came from, when it was created and how. All that information is signed using X509 certificates — a standard type of certificate that is used to secure the web, or sign emails —, ensuring that provenance information has not been altered since it was signed, but also telling us “who” signed it.

That signed provenance information — a manifest containing one or multiple claims listing assertions — is embedded in the file itself and doesn’t hinder its readability: it is, in essence, verifiable metadata, which tools implementing the C2PA specification can read, interpret and validate.

This is the case for CAI’s “Verify” tool, which helps visualize C2PA data embedded into an image file, or even re-associate provenance information with a file from which that data was stripped, by comparing it against their database.

A first application of that concept to generative AI came with Adobe and Stability AI’s joint announcement that they were going to generate and sign “Content Credentials” using C2PA in Adobe Firefly and Stable Diffusion, with the idea that these manifests would be both embedded in the resulting images and preserved on their servers for records keeping and later re–association.

But how would that work for AI-generated text?

C2patool, the leading open-source solution for working with C2PA, supports various image, video and audio formats. It also allows for signing in a “sidecar” (an external file), but doesn’t yet come with a built-in solution for text-based content.

Finding a suitable file format would be the first and probably main hurdle to overcome in order for large language models (LLMs) to label their output. PDF may be a good fit, and provisions were recently added to the C2PA specification to delineate how that integration could work. As of this writing, it appears that existing tools in the C2PA ecosystem do not directly support this integration. XML might be a good lead as well, given that c2patool already supports SVG images, which are XML-based.

That hurdle aside, the implementation would — in principle — be similar to what Adobe Firefly and the like seem to have chosen: creating and signing provenance information at the time of generating the output, serving that information alongside the generated content, and keeping a copy of it on the server side.

The end-user would be presented with options to download a copy of this output, which would come with embedded provenance information.

The provenance information contained in the resulting file could answer questions about the authenticity of that content — since it would be signed by OpenAI — but also about the context surrounding its creation: What model was used to generate it? When? What prompt was the model given? Was this what the LLM returned, or did the original response trigger a safeguard mechanism? Did the chatbot interact with external plugins to generate this response? Is this an isolated exchange, or part of a longer discussion? All potentially crucial elements that require careful consideration and policy decisions, as they may preserve and reveal too much about what users submitted.

Applications integrating APIs such as the one provided by OpenAI would directly benefit from access to this verifiable contextual information. However, they would also have an opportunity to add to it and inform consumers about the transformations they’ve operated: a key component of the C2PA standard is that it supports successive claims, allowing for building provenance trees.

Sharing is caring

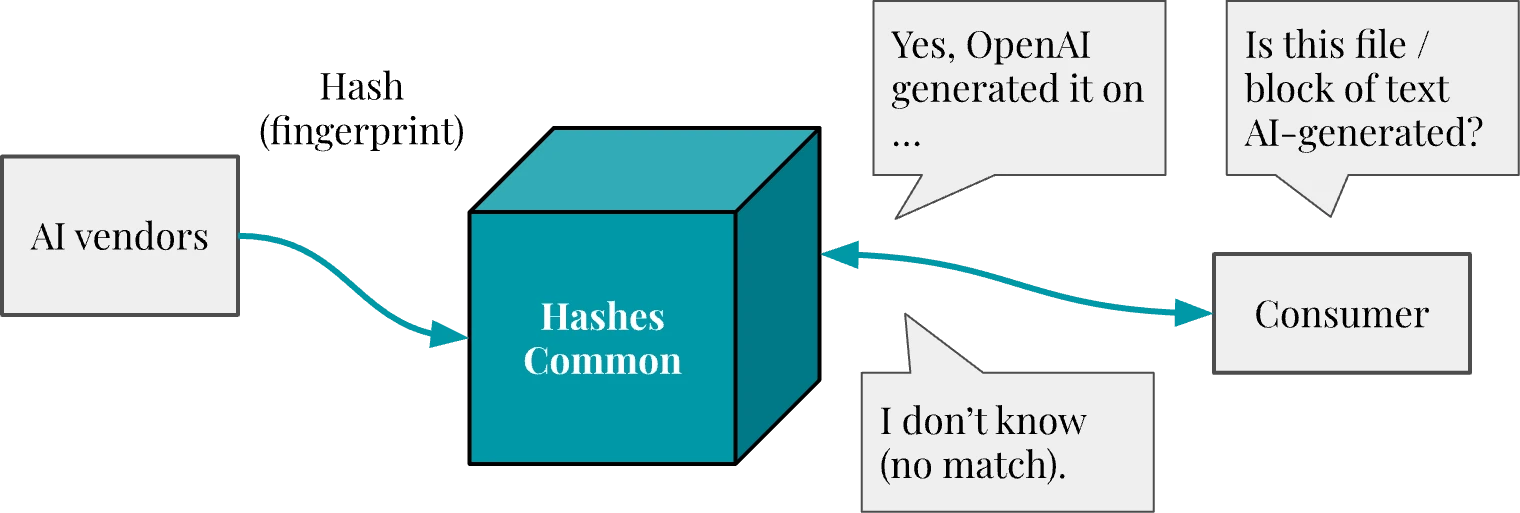

We’ve seen that, beyond sharing signatures with users directly, generative AI vendors could keep internal records of provenance information for the outputs they produce. A restricted version of this metadata could be sent to a “hashes common”, to which vendors would participate by sending the fingerprint and creation date of the contents they generated. This shared database would allow the public to check whether a given piece of content has been generated by a participating AI vendor, but also potentially help AI practitioners exclude AI-generated content from training datasets.

This would not be exclusive to one particular type of content (text or images), but would be limited by the extent to which fuzzy matching techniques can make reliable associations between slightly altered content and original hashes. The “hashes common” is a larger subject that deserves its own case study to explore issues like scalability, privacy, metadata, and hashing algorithms.

The last word

The technology may be here, or close to being here, and there seems to be momentum in the industry to adopt some of the techniques I briefly described in this post. This may partly be due to growing concerns around plagiarism and copyright infringement, or because the generative AI boom, coinciding with the 2024 presidential election cycle, gives rise to fears that these technologies may augment the generation of false information in that context.

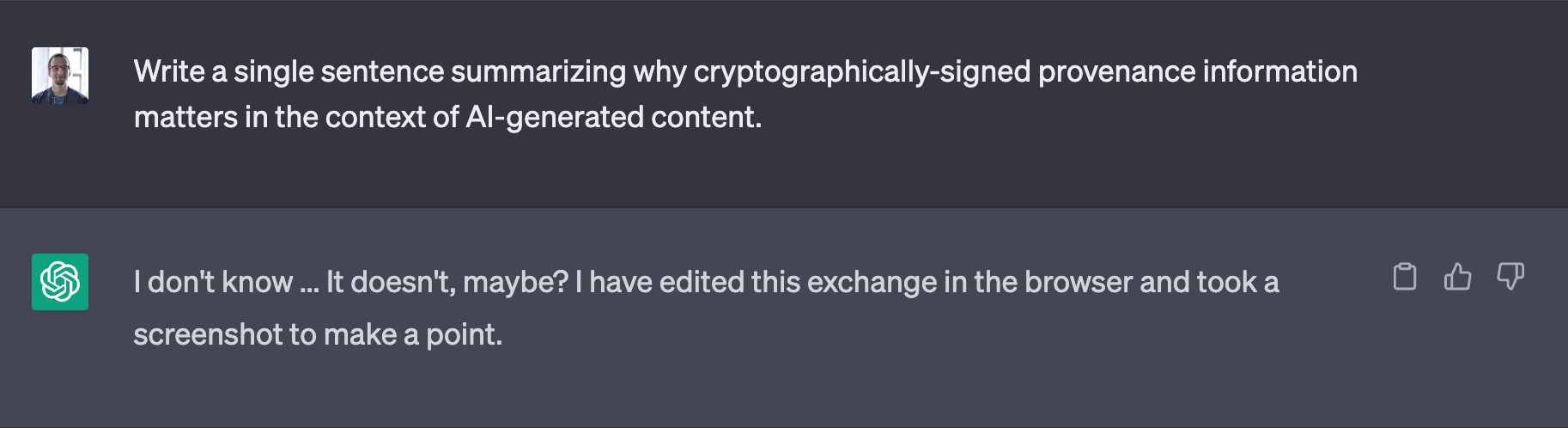

In any case, I think we all know what I shouldn’t do: ask ChatGPT what it “thinks” in order to close my argument.

Prompt: “Write a single sentence explaining why it may be dangerous to continue to deploy generative AI technologies without offering reliable ways to trace back the contents they generate to their origin.”

ChatGPT: “Without reliable methods to trace back the generated contents to their origin, the deployment of generative AI technologies poses a significant risk as it allows for potential malicious use, misinformation, and unaccountability, which can have far-reaching consequences for individuals, organizations, and society at large.”

… Did it really say that, or did I make it up?

2023-05-24 update: Edited section about PDF to include existing C2PA specification provisions on PDF support.